“And meanwhile it was April,

and the wisteria was here, blooming again.”

Pier Paolo Pasolini

There is no more apt phrase to enlighten our mind after the hard months we have faced: nature returns, always and in any case, bold and victorious. Nature takes back its spaces and leaves us enchanted, every time. The Bardini Garden with its famous wisteria pergola returns to amaze us. A poetic and fairytale journey through the scents of the Bardini Garden, shaded by the iconic wisteria.

“I remember one April. It overflowed

the heart like the wisteria from the walls.”

Sergio Solmi

The Bardini Garden: “the garden of the three gardens”

The antique dealer and collector Stefano Bardini (1836-1922), a frequent visitor to the Caffè Michelangelo and exponent of the Macchiaioli artistic movement spread in Florence and Livorno in the 1860s, coined the expression “the garden of the three gardens” to to define the history of the Bardini Garden in Florence with an intelligent synthesis.

The Bardini Garden in fact has a singular and eclectic constitution, which sees the combination of three gardens: the Anglo-Chinese wood, the Baroque staircase and the orchard.

Bardini Garden’s Lunette, Mauro Falzoni (inspired by the series of Lunettes by Giusto Utens, 1599-1602).

Restored in 2000 by the Parco Monumentale Giardini Peyron Foundation and by Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze, it was opened to the public in 2005. The Bardini Garden extends between Costa San Giorgio and Borgo San Niccolò, in a steep stretch of hill that declares its evident agricultural vocation.

Already in the 13th century, a building with a loggia and walled gardens, belonging to the Mozzi family, on the Montecuccoli hill is documented. The Mozzi bankers went bankrupt in 1303; the building was later purchased by the municipality of Florence, until, in the 16th century, the Mozzi family returned to possession of the eastern part of their ancient property. In the west, however, the Manadori had settled. The latter therefore commissioned the construction of Villa Manadora, in a panoramic position, to the architect Gherardo Silvani (1579-1675), of Florentine and Mannerist training.

In 1815, after a few changes of ownership, Villa Manadora was bought by Jacques Louis Le Blanc, governor of the Principality of Piombino in the Napoleonic era. It was Jacques Louis Le Blanc who initiated the works for the construction of the Anglo-Chinese garden, in the western part of the property.

In 1839, after centuries of division, the Mozzi family bought the entire property, including the part renovated by Jacques Louis Le Blanc.

On February 18th, 1915 the new owner became Stefano Bardini, who commissioned important structural changes: he had the walled gardens demolished, he ordered the creation of a driveway that would connect the various areas of the garden, he took care of the restoration of Villa Manadora and the construction of the Loggia del Belvedere, installing various statues of eclectic style and of Venetian origin. On the death of Stefano Bardini, the property passed to his son Ugo, who kept it until 1965.

The ticket to the Boboli Gardens includes the entrance to the Porcelain Museum and the Bardini Garden: you therefore exit Forte Belvedere and follow the short route that leads to the entrance of the Bardini Garden, from Costa San Giorgio 2. The route was baptized Florence Greenway and includes many other Florentine itineraries, all to be discovered: conceived starting in the 90s, it was defined by Antonio Paolucci as “the green thorn” of Florence. Today it includes 15 km between the Bardini Garden and the Viale dei Colli. In 2020, Firenze Greenway won the Tuscany Region Landscape Observatory Award; in 2021, Dr. Maria Chiara Pozzana, creator of the project, set up the Firenze Greenway Cultural Association.

Therefore, coming from the Boboli Gardens, you enter the Bardini Gardens from the west, from the entrance of Costa San Giorgio 2, and you come across the Anglo-Chinese wood laid out by Jacques Louis Le Blanc in the 19thcentury. Do not miss the collection of azaleas and the statues scattered in the garden, including the Canale del Drago, which has always been the mythical guardian of the gardens (just remember the snake Ladone of the Garden of the Hesperides, or the more modern and playful quote by Marco Dezzi Bardeschi at the Orti del Parnaso, in Florence).

In the immediate vicinity, where the canal winds its way picturesque, there is the couple of Ceres and Bacchus, divinities linked to nature, abundance and festivity. The fountain of Venus, on the other hand, acts as an eye-catcher in the lawn in front of Villa Manadori. This part of the garden is characterized by the shade of the English wood, alternating with the bright views of Florence.

Continuing in the garden, we arrive at the Belvedere, where Florence appears in its majestic beauty, literally at our feet. The vertiginous cascade of the Baroque staircase, lined with irises, roses and other blooms, plunges with a rush down and further down, up to the roofs of the city.

Behind the Belvedere, stands the Loggia, behind which there are a collection of camellias, the olive grove, the rose garden, the collection of viburnums and the Belvedere Grotto.

You reach the most famous part of the Bardini Garden: the splendid wisteria pergola that attracts countless visitors in April, for the spectacle of flowering. However, it is worth returning in June too: the precious collection of hydrangeas under the pergola will be at its peak. The wisteria pergola is inspired by the artistic season of the Cerchiate, already widespread in the Boboli Gardens, in the 17th century.

The “garden of the three gardens” is also the “wisteria of the three wisteria”: the three varieties that adorn the 70 meters of the pergola are in fact Wisteria Floribonda Black Dragon; Japanese Royal Purple with double purple and dark purple flowers and Showa Beni with pink flowers; Wisteria Prolific, the most widespread variety, with large purple flowers.

After the wisteria pergola, the most rural part of the Bardini Garden opens up: after the Rondò Belvedere, in fact, the orchard extends. The orchard includes espalier, cordon, full wind and dwarfed collections; there are apples, pears, plums, cherries and peaches.

Going down, you arrive at the Herms Niche and head towards the exit on Piazza dei Mozzi, after taking leave of the evocative statues of Vertumnus and Pomona, mythological deities associated with the change of seasons and fruit, painted in the 16th century by Pontormo in the Medici Villa of Poggio a Caiano, outside Florence.

Wisteria between art, history, and botany

The wisteria belongs to the Fabaceae family. Coming from China, Japan, Korea and America, it is a climbing shrub, rustic and resistant to cold. The branches of the wisteria twist around their supports and are therefore ideal for use as pergolas, treillage, walls and other types of garden furniture.

“To be or not to be. It’s like a wisteria leaning against a tree.”

Kô-an proverb

There are numerous variants of wisteria: among the best known, Wisteria sinensis (China); Wisteria floribunda (Japan); Wisteria frutescens (America).

The colour of the flowers varies from white to purple, passing through all shades of pink, mauve, lilac, lavender, blue. Flowering can occur in April, June or September, depending on the variety.

According to legend, wisteria was first seen by a westerner in 1816, in China. Captain Welbank was, in fact, having dinner at a rich merchant from Guanzhou (Canton). The banquet took place under a pergola full of wisteria, called by the Chinese Zi Teng, “blue vine”.

Captain Welbank managed to take a few wisteria seeds with him to England; a few years later, wisteria flourished in Europe. It was named Wistar in honor of a German anatomy professor and anthropologist named Kaspar Wistar, but the English pronunciation crippled the learned professor’s surname, and the shrub therefore became known as Wisteria. It was a botanical error, since the name Wisteria already existed: Linnaeus had in fact called Wisteria frutescens a plant from America, the American wisteria, in the 1700s. Nonetheless, the name remained Wisteria.

The name “glycine”, on the other hand, comes from the Greek and means “sweet plant“. It arrived in Italy around 1840.

A Piedmontese legend sees as the protagonist a sweet shepherdess named Glicine (Wisteria, in Italian) desperate for her unattractive appearance, so much so that she is consumed with tears, supported by a tree trunk. Her tears turned into clusters of flowers, and her body twisted around the trunk, giving rise to wisteria.

In Japan, wisteria is considered a symbol of friendship due to the indivisibility of its petals, as well as being synonymous with longevity and immortality, since it can live for several centuries. It has often been represented in painting in the screens (byōbu) and praised in the short verses of poetry (haiku).

Finally, we should mention the masterpiece “Genji Monogatari“, considered the first psychological novel in world literature (1002-1003), written by the lady Murasaki Shikibu (973-1014 ca.) in the Heian era, in the then capital of Japan, Kyōto. In a very refined game of fairy metaphors, the Princess of the Wisteria Pavilion is described (without ever naming her name), fourth daughter of the Emperor and high-ranking lady, loved by Genji, the shining one.

Detail of the screen “Birds and flowers of spring and summer”, Kanō Einō, second half of the 17th century, Santory Art Museum, Tokyo. (The screen was one of the works present at the exhibition “The Japanese Renaissance” at the Uffizi Galleries between 3 October 2017 and 7 January 2018).

“Fatigue:

Entering an inn,

the wisteria.”

Matsuo Bashō

“In the pale moonlight

The wisteria’s scent

Comes from far away.”

Yosa Buson

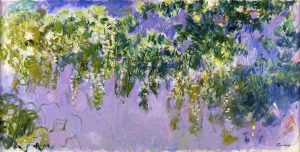

“Étude des glycines”, Claude Monet, 1919-1920, Musée de Dreux Eure-et-Loir, France.

Guided walks and tours in the wisteria of the Bardini Garden in Florence

Eager to inebriate yourself with the scents, views and colours of the Bardini Garden?

Know that you can keep the wisteria under control: on the Bardini Garden website, the webcam‘s eye on the wisteria bloom is always watchful!

However, when you can travel again, don’t just observe the blossoming from a virtual window …

Paint your palette of wishes in the company of a tour guide: I will be happy to accompany you to the Bardini Garden, show you its history and its botanical collections.

For information, write to: info@myfloraguide.com

“In my home

They blossomed in waves

The wisteria flowers

And, mysteriously, it lingers

Like a wave

Even those who watch them.”

Oshikoshi no Mitsune (898-922)

Bibliography:

Dal Pra, E., “Haiku. Il fiore della poesia giapponese da Bashō all’Ottocento”, Arnoldo Mondadori Editore S.p.A., Milano, 2011.

Cattabiani, A., “Florario. Miti, leggende e simboli di fiori e piante”, Arnoldo Mondadori Editore S.p.A., Milano, 2017.

Menegazzo, R., Hiroshi, A., Minoru, W., Tadahito, T., “Il Rinascimento giapponese. La natura nei dipinti su paravento dal XV al XVII secolo”, Giunti Editore S.p.A., Firenze, 2017.

Pozzana, M., Mezzapesa, C., Tarassi, T.,“Firenze Greenway. Giardino Bardini, Viale dei Colli”, Casalta s.a.s., Firenze, 2014.

Pozzana, M., “I Giardini di Firenze e della Toscana”, Giunti Editore S.p.A., 2011, Firenze.

Pozzana, M., “Giardino Bardini”, Casalta S.a.s., Firenze, 2013.

Shikibu, M., “La storia di Genji”, Giulio Einaudi Editore s.p.a., Torino, 2012 (traduzione di Maria Teresa Orsi).

Tangorra, M.C., “Il Giardino e la Pittura”, Angelo Pontecorboli Editore, Firenze, 2011.

Useful links:

www.uffizi.it/eventi/il-rinascimento-giapponese